Back To The Future

SURF:

Good times this week as fun surf was met with great conditions. For the upcoming weekend, a pattern change is occurring in the Pacific which looks eerily like our weather in December- high pressure above Hawaii is pushing storms towards Canada, then they head due S towards California. The result? Storms that are 1/2 over land and 1/2 over water- which gives us showers and mostly a NW wind/groundswell mix. How is this different than the epic January we experienced? High pressure was nowhere to be found and storms that formed off of Hawaii headed straight towards us. That equaled more rain and bigger groundswells. With that said, Friday looks to be a repeat of today with waist high+ background NW/SW groundswells and clean conditions.

On Saturday, a cold low pressure from the N will head our way and increase the NW windswell. Look for chest high surf in the morning (get on it EARLY) and overhead sets by dark. Winds should start out from the SW, then turn W by evening. On Sunday, low pressure exits the region with dropping shoulder high sets and NW wind. And here are tides, sunrise/sunset, and water temps for the next few days:

- Sunrise and sunset:

- 6:35 AM sunrise

- 5:32 PM sunset

- Water temps are high 50's.

- And tides aren't doing much this weekend

- 1.5' at sunrise

- about 3' at lunch

- and back down to 1.5' at sunset

FORECAST:

Good news and bad news. Good news? More NW is coming. Bad news? It's more of that northerly windswell. For Monday, the NW over the weekend drops to the chest high range before our next cold low pressure moves in on Tuesday. Look for more overhead bumpy NW windswell by Tuesday evening and dropping quick on Wednesday.

On its heels is more overhead NW windswell by late next weekend. Hopefully each successive low pressure system from the N will start to breakdown high pressure over Hawaii and we'll get back to the ideal wet weather/big surf we had in January.

WEATHER:

As mentioned above, we have some weak low pressure systems headed our way from British Columbia that are partially over land. The result is not a lot of moisture for rain. Friday is our last day of sunny warm weather as clouds increase Saturday and last into Sunday. We've got another low pressure system mid-week and yet maybe another one next weekend. Here's a quick summary of the week ahead:

- Sunny Friday and temps around 70.

- Clouds and a breeze Saturday and MAYBE light showers? Temps will struggle to hit 60.

- Clearing and cool Sunday with temps near 60.

- Monday is clear and low 60's

- Increasing clouds on Tuesday and maybe showers late. Temps again may be near 60.

- Clearing Wednesday and cool again.

- Thursday/Friday sunny and cool.

- Maybe showers again next weekend?

If anything changes between now and then, make sure to follow North County Surf on Twitter!

BEST BET:

Early Saturday before the wind picks up or it's anyone's guess next week with new NW wind/groundswells and low pressure systems headed our way...

NEWS OF THE WEEK:

As we continue with our list of top 5 'sketchiest' waves in California, we've already hid under the covers from #5 Ghost Trees and #4 Tijuana Sloughs. Scared yet? If not, here's a spot I touched on in the past. I apologize, it's a loooooong read, but well worth it. Coming in at #3... Potato Patch (trust me- it's scarier than it sounds).

The waves off Ocean Beach San Francisco have always amazed me. And not in a good way- there's A LOT of weird stuff going on out in the ocean up there. On a big day (20'+), surfers have to deal with the shore break (duckdiving an 8' gun in 8-10' closeouts is insanity to me), then dodging 20'+ sets at a shifting beach break no less, then you've got those creepy 40'+ phantom sets a mile or so out to sea. No thanks.

The bathymetry is constantly changing do to its history. About 600,000 years ago, the Central Valley of California was one big lake called Lake Corcoran and it drained out through what is now the entrance to San Francisco Bay. The lake was roughly 12,000 to 19,000 square miles. As you can imagine, all of that water draining through the Bay made some wild sandbars, seamounts, etc. For comparison's sake, for those of you that surf the river mouth at Ponto, that lagoon is only 610 acres- roughly 1/20,000 the size.

Even though Lake Corcoran is gone, the bathymetry remains and San Francisco Bay is still making sandbars. At 550 square miles, it's still considerably large enough to make some interesting sandbars- like the alpha male of all sandbars- the infamous Potato Patch which comes in at #3 California's 'Sketchiest' spot.

Just offshore from the mouth of the San Francisco Bay, Potato Patch gobbles up ships like they're popcorn. The shoal is part of the larger Four Fathom Bank outside of the San Francisco Bay and is the northernmost area of San Francisco Bar alluvial silt deposits. Waves breaking over the shoal are visible at low tides from the coastal hills in the Golden Gate National Park. Surfline describes the area as "creepy - a minefield of shifting, throwing peaks, extending from a couple of hundred yards offshore all the way to the horizon. During a giant swell in the Potato Patch, you will stare at nature in all its beautiful evil." The Potato Patch was named for the 1800s potato farms near Bolinas Lagoon which shipped to markets in San Francisco: "Occasionally a potato boat would capsize on the sand bar, spilling its load".

Legend has it, only 3 people have attempted to surf it; Santa Cruz chargers Perry Miller and Doug Hansen towed it in the late 90's and SF legend Mark 'Doc' Renneker tried to PADDLE it. Sit back, crack a cold one, and take the afternoon off to read this unbelievable story from the San Francisco Gate newspaper:

A strong wind had just started howling east as Mark "Doc" Renneker passed beneath the Golden Gate and headed out to sea. In the distance, giant ribbons of waves exploded on the Potato Patch, a shipping hazard 2 miles off the tip of the Marin Headlands. Renneker had forecast a 20-foot northwest swell, but he could see his estimates were off. Way off. Set waves were easily in the 30- to 40- foot range on the face and the outgoing tide would only make them bigger. Eddie T., the boat's captain, pointed his Boston Whaler right and headed for the whitewash.

As the boat trolled in circles, wind chop clapping violently against its prow, Renneker studied the swells, lifted his 9-foot Parish big wave "gun" surfboard and readied to jump in. But by now the wind was blowing so hard that smaller 5-foot waves had pocked the faces of bigger waves, creating an impassable maze of whitewash moguls. "There was just too much swell, too much wind," Renneker says. "We decided to get out of there."

Later that day, a fishing boat capsized where Renneker had planned to surf. One man drowned; three others were rescued by the Coast Guard.

This was 1981. Since then, "Doc" Renneker has spent 25 years researching the Potato Patch and the Great Bar of the Golden Gate -- tracking currents, plotting entry points, waiting for the right winter storm to return. And when it does, he plans to be the first person to surf what could be one of the wildest and most baffling surfbreaks on Earth.

But first he needs to find a way there. "I realized after awhile that it was too dangerous for a boat to be there," he explains casually, leaning his 6-foot-4-inch frame over the worn, wooden dining table of his Ocean Beach apartment. "You know, when I was out there, I kept thinking about the boat driver, the other people I was with," he pauses. "It seemed better just to paddle out there next time."

Such casual bravado in the face of a seemingly impossible feat -- roundtrip to the Potato Patch requires at least 3 miles of paddling in the open ocean; if hypothermia doesn't get you, a Chinese freighter will -- might seem like a put-on, but Renneker can get away with it. The same way he can get away with wearing black socks with flip-flops in winter and plastering his apartment with photos of himself surfing. For 30 years he has tackled the treacherous surf of Ocean Beach between Sloat and Pacheco, often the only one to make it out on the most tumultuous days. He was one of a handful of surfers to first attempt Mavericks, and participated in the first Mavericks contest in 1999. At 54, he has an international reputation for taking on some of the biggest and most brutal cold-water waves in the Western Hemisphere. But it is the distant, stupefying Great Bar that has become his obsession for more than three decades.

"I was flabbergasted," he says, recounting the first time he saw the Potato Patch break in a winter storm. It was 1974 during his first semester at UCSF attending medical school. While dissecting a cadaver on the 14th floor of the anatomy lab, he paused to look out the window. "There were these consistent beautiful waves breaking miles out in the open ocean north of the Golden Gate. They were so ordered ... but in a different kind of order, a larger order," he says. "I became a student of it and started cooking up a strategy to surf it."

The first attempts

The Potato Patch is the northern lobe of the Great Bar sandbar, which curves down from the Marin Headlands to the middle of Ocean Beach, surrounding the Golden Gate like a giant left parenthesis. The unsubstantiated legend is that the Patch got its name in the 1850s when a produce ship from Bolinas sunk there, filling the bay with thousands of, you guessed it, potatoes. Others say it was so named because "it looks like a bunch of potatoes rolling over one another" during the shifting tides. Either way, it's a formidable shipping hazard, sinking numerous ships and creating general havoc for sailors for hundreds of years.

Since the Great Bar is unbuffered by any other landmass, it receives an incredible amount of energy from open sea swells, especially in winter. Then, waves that Renneker projects can reach up to 80 to 100 feet in height roar in from the north and crash with atomic force on its shallow shoal. The Potato Patch in particular produces what Renneker considers "rideable" waves about five days a year, when the swell is milder -- around 20 to 30 feet -- tides are low and the wind is calm. Too much outgoing tide can quickly suck you out to sea; too much incoming tide will throw you into the path of building-size waves. When all the swells, tides and winds line up, it's time to head out.

Jan. 9, 1983, looked like one of those days. Renneker had been tracking a new swell coming in from the west-northwest. It was slated to enter San Francisco at about 20 feet with minimal winds. He rounded up the same group that had gone out in 1981: boat captain Eddie Tavasieff -- "Eddie T." -- a San Francisco commercial fisherman since 1972, and fellow big wave surfer Bill "Peewee" Bergerson. That morning they loaded into Eddie T's 21-foot Boston Whaler and motored west.

At first, Renneker wanted to try the "South Patch," the south tip of the Great Bar located about 3 miles from Noriega at Ocean Beach. "We paddle out from the boat, got mowed over by huge waves, sucked out to sea, barely made it back in the boat, that kind of thing," Renneker says, lackadaisically. "Then we headed to the Potato Patch."

As the Whaler approached from the west, Renneker could see that conditions were better here, though the swell was still churning up waves about 30 feet on the face, each as disorganized and powerful as any wave he'd seen. "I didn't want to turn back without trying it, like in 1981," he says. Renneker grabbed his board, steadied himself in the violently rocking boat, and jumped into the water.

Feathering to the west, a gray-green mountain lifted from the sea, bending the horizon in steeper angles every few seconds, doubling, then tripling its size as it approached. Renneker turned his oversize board and hurried out to its path, turned again and paddled feverishly as the wave lifted him four stories skyward toward its peak. He lifted himself up to place his feet on his board. But his board wasn't there. It had fallen out from below him, and was now dangling in midair. He followed, skidding down the 40-foot wall of water on his back, his stomach, his face. When he emerged, his wetsuit hood was pulled completely around his face, his contact lenses lost; he was dizzy, out of breath.

"I thought, 'Oh My God. Let's get out of here,' " he says. Crawling into the boat, Eddie T. turned and left before the next set rolled through. On the way back they passed a whirlpool -- "a real whirlpool," Renneker emphasizes, and Eddie T. confirms -- sucking up huge branches felled by the last winter storm. "It was just otherworldly out there, just crazy," he insists. "That tabled the attempts for a period of time." It would be eight years before Renneker attempted again to surf the Great Bar of the Golden Gate.

Reflecting on the trip years later, Renneker figured out that it wasn't the tides, location or huge waves breaking over a shipping hazard in the middle of the ocean that made surfing the Potato Patch so difficult or so dangerous. It was the boat. "When you take a boat or Jet Ski out [to a surfbreak], you don't really know what you're getting into," he says. "And that can be dangerous."

To Renneker, the southern tip of Great Bar, the South Patch, was a better place. He believed if he could paddle out the 4-plus-miles "under his own will" to the South Patch, he would have time to better study the waves, intimately feel how the tide was pulling, how the currents were shifting. And if he could make it, and catch a wave, he would still be the first to surf the Great Bar.

Another go at it

The South Patch continues where the Potato Patch ends, extending from the center of the Golden Gate then bending east into Ocean Beach, filling in between Noriega and Sloat. (It's this sandbar that is partially responsible for creating the towering Pipeline-like tubes that sprout up between these streets a few days a year in the winter storm season.) Separating the Four Fathoms and South Patch is a shipping channel that is regularly dredged by the Army Corps of Engineers to make it deep enough for cargo ships to enter the bay. This dredged sand is dumped at the south lobe of the Golden Gate sandbar, resulting in a shallow shoal upon which enormous swells lunge and break. This is the South Patch. Waves here can reach a purported 10 stories high, but Renneker believes they are rideable at half that size. "It's an amazing wave, probably the only wave in the world that would let you be on a 30-, 40-, 50-foot face and let you ride it for a mile, or two miles," he says.

At the end of February 2005, Renneker had been tracking an enormous swell in the Pacific, a strong west-northwest at around 20 feet, heading straight for Ocean Beach. He alerted longtime friends and fellow big wave enthusiasts Bob Battalio and John Raymond. It could be the swell they'd been waiting for for 20 years. On the morning of March 2, 2005, it arrived. At 10:30 a.m. Renneker, Battalio and Raymond met up in the parking lot across from the zoo, unloaded their surfboards, zipped up their winter wetsuits and headed down the sand embankment to the water. Their plan was to paddle out at Sloat in the outgoing tide, when water rushes south from the mouth of the bay. Renneker predicted that by doing this they would not be unwittingly sucked off course and out to sea like they had been in a failed attempt to reach the South Patch in 1991.

"We paddled for about an hour, just to get outside the break," explains Raymond, a 47-year-old bankruptcy lawyer and Renneker's longtime friend. "It was a massive day."

Battalio made it out first and waited for the group in the buffer zone between the crashing shore break of Sloat and the open sea waves of the South Patch. He was unable to keep his position in the outgoing current and began drifting south. So were Renneker and Raymond as they continued to fight against the consistent walls of whitewater pounding into shore. Two hours later the group had drifted 2 miles, past the zoo and Fort Funston. "We ended up in Daly City," says Raymond. "We met up there then started paddling north."

Renneker had predicted that if the group paddled out in the outgoing tide and hustled north, they could possibly reach the South Patch at slack tide, which would enable them to paddle around the South Patch and find a good position to enter the swells without getting sucked into the waves or out to sea.

"As we approached [the South Patch], I remember hearing this really low rumble," Raymond recounts. "I looked up and there was this wave, a perfectly shaped Hawaii 5.0 wave, breaking a mile out from us. It was maybe 50 feet, 70 feet on the face, just Hawaii 5.0ing down the line," he says. "It was one of the most spectacular things I've ever seen."

At this exact time, the world was awing as 24 other big wave surfers competed to take on "The World's Most Dangerous Wave" at the annual Mavericks competition. Thirty miles north, Renneker, Raymond and Battalio were paddling 4 miles out in the open ocean, in waves possibly twice the size.

As the group jostled for position, trying to stay out of the path of the incoming waves that were now breaking from various, unexpected directions, Battalio, a 47-year-old coastal engineer, didn't panic. "You've got a heightened sense of awareness out there, a keener sense of what exactly is going on," explains Battalio. "We were looking around, paddling around, trying to find where the waves were breaking ... and then we realized, we were right in the middle of it."

It's this heightened perception that made Raymond aware of how truly dangerous it was out there, of how the wave-hunter could become the wave-hunted in a moment's notice. "It was a really creepy feeling after awhile," admits Raymond. "You realize as these huge waves are passing by you, that if you take one of them on the face, you would probably break your leash, be pushed 50 feet underwater, lose your board, then swim for three hours, maybe have to swim to Pacifica," he stops. "And if the tides were too strong, maybe you couldn't swim at all."

Neither Renneker, Battalio nor Raymond caught a wave that day. After five hours and an estimated 10 miles of paddling against the outgoing and incoming tides, torrential currents and swells, they gave up and made their way back to Sloat. "But it was extremely helpful," Renneker says, defiantly. "I learned my lineups, where the right spot to be was when we returned -- and we all agreed to try it again when the conditions were right."

That other break

It's these otherworldly descriptions of the Great Bar, of waves so unbelievable, so local, that ring strangely similar to the descriptions of another Bay Area surf break "discovered" 15 years ago.

n 1975, Jeff Clark paddled a half-hour out from the cliffs off Half Moon Bay to surf the seldom-breaking, little known freak-wave called Mavericks. By the late 1980s, it was still a relative secret, with only a handful of local surfers believing it and even fewer attempting it. But in a community where members can't help boasting the exact location of a "secret spot" almost as much as they can't help boasting of an "epic" ride, nothing stays off the surf map for long. By 1992 photos of the monster waves at Mavericks had made it to Surfer Magazine, and soon hordes of surfers and their wool-cap-wearing spectators stumbled down Pillar Point to see this magnificent wave. Since then Mavericks has become the most famous cold-water surf break in the world.

"There are 50 different Mavericks out there," Renneker explains about the Great Bar. "And unlike Mavericks, which trips over a reef, jacks up and is not a natural surfing wave, the South Patch is a classic surfing wave, something from Hawaii, that you could ride for minutes -- that's the allure."

Battalio, who as a coastal engineer has been studying the Great Bar for decades, does not doubt the size and quality of the waves on the Great Bar rival -- even exceed -- those of Mavericks. "Waves get beyond 50 feet out there, I'm sure that happens, and I'm approaching this with education in this topic," he says plainly. "But as far as it becoming another Mavericks, that's difficult. It's much less accessible and a very difficult wave to photograph -- without that, people might not really see the attraction."

Battalio's and Renneker's unassuming explanations of a feat so ridiculously dangerous come off as confusing at times, especially for this group, who other than having a penchant for wearing flip-flops and shorts during chilly rainy days, seems the opposite of the slacking, spaced-out, "surfer" image many of us have come to affiliate with the sport. Both Battalio and Raymond are approaching 50, married with two kids each, holding professional jobs. Even more perplexing is Renneker, who, when he is not surfing 50-foot-waves, shares his home with Jessica Dunne, his partner for 33 years, and makes his living as a family physician and associate clinical professor at UCSF. He's also the author of "The Biology of Cancer Sourcebook" and "Understanding Cancer," both top-selling university texts.

But the one thing that sets all of them apart is the certain look each has recounting big wave adventures. It's a contrary gaze, one crossed between the spaced-out 2,000-yard-stare of a Vietnam vet and the acute, exacting glance of a microsurgeon at work -- eyes both focused and distant, as if they've seen things they shouldn't have ... and lived to tell about it.

The final attempt

Raymond kissed his wife goodbye on the morning of Feb. 7, 2006, loaded his board in his car and headed up to meet Renneker and Battalio at Ocean Beach. A freak swell had been brewing off the coast of Japan and had slowly trolled across the Pacific for a week. That morning it was to hit San Francisco at more than 20 feet with no wind predicted, with buoys at about 15-17 feet every 20 seconds. The perfect storm. "It was one of those once-a-decade swells -- the cleanest we've ever seen," Renneker explains. Mavericks was also held this day, its organizers later calling it the best conditions "in big-wave surf contest history."

At 10 a.m., Renneker, Battalio and Raymond met up at Kirkham with the plan to paddle out in the incoming tide, in the hopes of reaching the South Patch in the slack tide. But again, they had underestimated the fierceness of the paddle out. "There was so much energy coming in there, that the impact of the waves were creating currents of their own that were pushing us north," explains Battalio. "We battled it for about an hour."

While Battalio was battling the shorebreak, finally making it out midway between Lincoln and Fulton, Renneker was being dragged quickly north toward the Cliff House. "My concern with being in front of the Cliff House was all of those looky-loo tourists," Renneker explains. "The last thing I wanted was for them to see me and call the Coast Guard or something ... then you're dealing with helicopters and rescuers and all that."

By the time Renneker had made it to the Cliff House, Raymond had given up. "I got dragged about 3 miles north, all the way to Seal Rock and said 'screw this,' " explains Raymond. "I turned around, paddled in and just went down to surf Mavericks."

As Renneker and Battalio waited at separate points, they grew agitated -- each knew there was only a small window of time to make it out to the South Patch before it became ravaged in the outgoing tide. "I had been sitting there [off the tip of the Cliff House] and had to decide if I was going to go out to the South Patch alone," explains Renneker. As the tide shifted, rivers of flowing water shot from the Golden Gate like fingers reaching for open sea. Renneker figured if he could paddle into one of these rivers, he could ride it out to the South Patch. "It was revelatory," he explains. "I paddled in, just sat there and it took me." A half hour later he was in the middle of the South Patch.

"I had all my markers from last year: Mount Tam, the Golden Gate, Land's End. I knew where things were going to line up, I knew where I needed to be," he explains. Within minutes , an enormous wave rose on the horizon. "I figured, from the size of it, I had about 2 minutes to paddle out to it, if I was going to catch it." As the wave approached and arched itself over the shallow shoal, Renneker turned his 10-foot-6-inch Randy Cohn four-fin gun surfboard and paddled in. He caught it.

"It was a big, big, big wave. Much bigger than any wave I've caught at Mavericks," he explains. He first steered left along the lip, being cautious not to drop too far down the enormous face. As he rode left, the wave buckled and shifted beneath him. "I went down this extraordinary ledge," he says, his voice, which is otherwise stern and emotionless, gets faint here. "I was going as fast as I've ever gone on a surfboard." Then a whole new wave stood up and reformed beneath him. "I just glided along, I don't know for how long, just rode this amazing wave until the whitewater dissolved back into pure, green-blue."

Renneker took his markers. He had ridden about one-third of a mile. "I remember sitting there in the open ocean, just laying on my board, thinking," he speaks, softer now. "Well, it's been 25 years for this moment," he says. "I was, God, I was just elated."

He had just become the first person ever to surf the Great Bar of the Golden Gate.

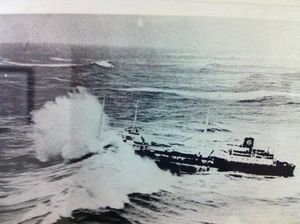

PIC OF THE WEEK:

Just a 'small' day at Potato Patch, a few miles out to sea, in the middle of a shipping lane, notorious for great whites, currents, fog, 50 degree water, wind prone (to say it mildly), AND a minimum 1 hour paddle out if you're lucky. Nothing to see here. (But if you do want to take a peak at some more scary Nor-Cal surf, check out Jack Bober's work here).

Keep Surfing,

Michael W. Glenn

Sage

Dept. Of Defense Shot Down My Kid's Birthday Balloons

Even I Could've Won Pipe This Year

Michael W. Glenn

Sage

Dept. Of Defense Shot Down My Kid's Birthday Balloons

Even I Could've Won Pipe This Year