Turn and face the strange. Ch-ch-changes!

SURF:

Days are getting shorter. Mornings are a little crisper. NW swells have suddenly appeared. Fullsuits are the norm. And birds are headed S for the season. Notice the ch-ch-changes? (With apologies to Bowie). Fall is officially here. For tomorrow into the weekend, we've got some late season SW showing up and early season NW.

Look for new small NW/SW combo tomorrow for waist high surf and chest high sets at the best combo spots. That lasts into Saturday.

For Sunday, we have slightly better SW showing up for waist to chest high surf. Nothing major this weekend but we'll at least have waves around town. And here's the tides, sun, and water temps for the next few days:

- Sunrise and sunset:

- 6:40 AM sunrise

- 6:40 PM sunset

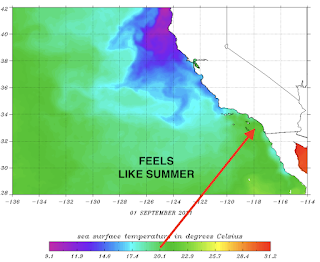

- Water temps are hovering in the mid-60's and fullsuits will be the norm until June unfortunately.

- And tides are pretty simple this weekend:

- 2' at sunrise

- 5' at lunch

- 1.5' at sunset

FORECAST:

Let's get the easy stuff out of the way: Nothing from the tropics. Again. And there probably won't be until next summer since La Nina is in control.

On the bright side, we've got fun leftover SW in the water on Monday along with a new fun NW. Look for chest high combo swell with the best spots hitting shoulder high.

We then get a reinforcement from a better NW late Tuesday for shoulder high waves in SD that spills into Wednesday.

Late next week is on the smaller side but we will still have rideable combo swell in the line ups.

And if the models are correct, we could have a good late season SW arriving around the 10th for shoulder high surf around here and overhead sets in the OC. Hoping to flip on the EBS again...

WEATHER:

Nothing exciting on the weather front this weekend which is fine by me- don't need any Santa Anas adding fuel to the fires.

And for you fans of snowboarding, the Northern Rockies got snow last week- actually, the last day of summer. So you got that going for you. For us down here, we've got a weak low pressure system setting up shop this weekend for more low clouds and cooler temps. That will exit after the weekend but look for the cooler temps and night/morning low clouds to stick around next week. If anything changes between now and then, make sure to follow North County Surf on Twitter!

BEST BET:

Monday with fun combo swells or Tuesday/Wednesday with fun NW!

NEWS OF THE WEEK:

In its simplest form, surf comes from storms. And most likely, low pressure systems- like the ones that form in the Aleutians, off Antarctica, or those pesky hurricanes near Baja. But when we say 'low pressure', just what are meteorologists referring to? Here's a rundown from our friends at Accuweather:

There are quite a number of scientific terms commonly used in weather forecasting and low pressure is one of the most widely used terms. However, many people may not be exactly sure of what a low pressure area is.

Quite simply, a low pressure area is a storm. Hurricanes and large-scale rain and snow events (blizzards and nor'easters) in the winter are examples of storms. Thunderstorms, including tornadoes, are examples of small-scale low pressure areas.

There are quite a number of scientific terms commonly used in weather forecasting and low pressure is one of the most widely used terms. However, many people may not be exactly sure of what a low pressure area is.

Quite simply, a low pressure area is a storm. Hurricanes and large-scale rain and snow events (blizzards and nor'easters) in the winter are examples of storms. Thunderstorms, including tornadoes, are examples of small-scale low pressure areas.

On a weather map, low pressure areas are label with an "L" and high pressure areas are labeled with an "H." A low pressure area usually begins to form as air from two regions collides and is forced upward. The rising air creates a giant vacuum effect. Hence, a zone of low pressure is produced with the lowest pressure near the center of the storm. As a storm approaches a particular area, the barometric pressure will lower. In some sensitive people, body aches may be more severe due to the pressure change.

As the air in the storm rises, it cools. As the air cools, moisture within the air condenses to form clouds and rain and snow. Falling barometric pressure, or the approach of a low pressure area, is often an indicator of rain, ice and snow arriving soon. As the amount of rising air increases, air must rush in from the sides to replace the rising air near the center of the storm. The more violent the rising air near the center, the faster the air must rush in from the sides. This is what sometimes creates strong winds.

The rotation of the Earth creates a force that causes the rushing air coming in from the sides to spin counterclockwise in the Northern Hemisphere and clockwise in the Southern Hemisphere. In some rare causes, tornadoes may rotate clockwise in the Northern Hemisphere. This is because tornadoes are a very small-scale storm.

Often as a storm approaches, winds blow from the south or east. Often as a storm departs, winds blow from the west or north. This rotation is what helps to pump warm air in ahead of the storm and draw cold air in behind the storm. For example, in the winter, snow may turn to ice and rain as a storm approaches, then rain may end as snow or flurries as the storm departs.

In some of the most violent storms, such as hurricanes, typhoons and Indian Ocean cyclones, a doughnut-shaped area of high winds with rising air occurs near the storm center. However, right at the center of the storm, the air sinks enough to tame the winds and sometimes cloud-free conditions. This is called the eye of the storm.

Make sure to remember this when storms arrive this winter as there may be a pop quiz.

BEST OF THE BLOG:

As a reminder, the North County Board Meeting is back at it again tomorrow, Friday, September 24th. As a refresher, the NCBM is a group of business professionals looking to make our community a better place. And you can too. There's no cost to join- you just need to be a surfer. So if you're reading this, you probably qualify. And no skill required either! Whether your a first-timer on a foamy or competed on the World Tour (you know who you are), come on down to Seaside Reef tomorrow (Friday) from 7 to 9 AM to:

- network

- grab some breakfast

- check the surf

- and find out how you can help support your community at our next charity event

Just look for the tent on the beach. Please contact me at northcountyboardmeeting@gmail.com with any questions.

Keep Surfing,

Michael W. Glenn

Uncanny

Got All Kinds Of Friends Now That I Won The Lottery

Inventor Of The Huntington Hop, Waimea Wiggle, And Shark Island Shimmy

Michael W. Glenn

Uncanny

Got All Kinds Of Friends Now That I Won The Lottery

Inventor Of The Huntington Hop, Waimea Wiggle, And Shark Island Shimmy