SURF:

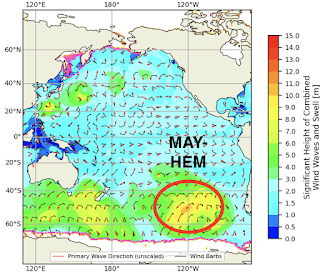

Well wasn't that a dud. Actually, let me rephrase that- Congratulations Orange County! The supposed solid swell that was to light up the OC and send us a smaller version last weekend really did light up Camp Pendleton and sports north. And down here? Not really. Even though the storm looked promising on the charts, it had too much of a southerly angle unfortunately and passed right by us. And to add insult to injury- the clouds never cleared in SD! So what's a surf forecaster to do? Try again I guess. So here goes:

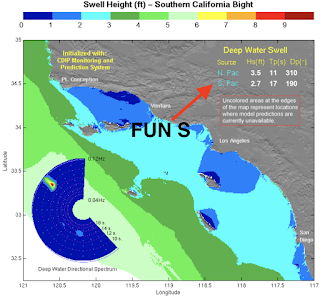

We've got a new small SSW swell building Friday for waist high surf with chest high sets towards the OC. On its heels is a small bump in NW windswell on Saturday. Most everywhere should see chest high sets from the combination of swells.

On Sunday... we have a new S swell filling in again (better towards the OC of course) as well as a late season chest high+ NW groundswell from the Aleutians. The S will be better towards the OC and the NW in SD... so what about us stuck here in the middle of north county SD?! Hopefully we'll see shoulder high sets from the combo. We deserve it after last weekend's debacle. One item of note- we may have a weak cold front move by the N this weekend so winds may be an issue out of the SSW- most likely strongest by Sunday. So we've got surf- but wind also possibly. And here's the tides, sun, and water temps for the next few days:

- Sunrise and sunset:

- 6:01 AM sunrise

- 7:31 PM sunset

- 13.5 hours of sunlight!

- Water temps have been FRIGID lately due to the clouds earlier in the week and NW windswell. Most spots were 58! But with the sun this weekend, we should be back to the low 60's.

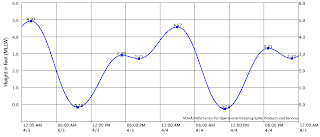

- And the tides this weekend are a little odd:

- -0.5' at sunrise

- and pretty much 3' by mid-afternoon...

FORECAST:

The shoulder high NW/SW from Sunday continues on Monday and we may have cleaner conditions too.

Most of next week looks to be waist high+ from the NW/SW then models show more NW windswell towards Saturday for chest high sets.

By Sunday, we should see more consistent chest high surf from a new SW.

And farther out... forecast charts show a good south taking shape in the next few days which would put a shoulder high sets from the SW at our beaches around the 13th. Just need those S winds to stay away!

WEATHER:

Nice to see a couple showers early in the week. We only had 1/10" at the beach but the foothills got 1/4" and even a dusting of snow at the highest peaks. That's gone of course and our great weather today will roll into Friday with more sunny skies and temps in the high 70's. A weak cold front starts to roll to the N on Saturday and our temps drop to the high 60's along with more low clouds/fog down here. By Sunday, the low pressure kicks up our winds to the 10-15 mph range from the SW and temps hit the mid 60's- 15 degrees colder than Friday! Slight high pressure builds early next week for temps again back in the low 70's and less low clouds/fog. If anything changes between now and then, make sure to check out North County Surf on Twitter here!

BEST BET:

Tough call as this weekend will have waves but winds could be an issue. Or wait until next weekend with more SW and cleaner conditions? Or a bigger SW towards the 13th?! Only way to find out- surf them all!

NEWS OF THE WEEK:

Heard the saying 'Only a surfer knows the feeling'? How about 'Only a surfer sees pelicans surf'? You know what I'm talking about: Pelicans seemingly doing a floater above the lip of a wave and gliding forever. How do they travel so far with out flapping their wings? Seems as though they're good at doing airs (or riding air) as well as flying. Here's the San Diego Union Tribune to elaborate:

Take a walk along the beach in San Diego County and you’re likely to end up marveling at the majesty of birdlife. Sleek brown pelicans descend from the sky and glide — often hundreds of yards at a time — just above the ocean’s surface, in front of building waves. It’s a common phenomenon that was not deeply understood — until now. UC San Diego has come up with the most detailed theoretical model yet for describing and quantifying how pelicans harness the ocean and winds with little or no need to flap their wings.

The bottom line: pelicans — which have wingspans up to 7.5 feet wide — are fantastically skilled at gliding atop the updraft of wind that is created by moving waves. The waves get steeper as they near shore, further strengthening the updraft. The bigger the wave, the bigger the lift. And pelicans know it; they get as close as possible to the ocean’s surface, where the updraft is strongest. It’s not unusual for a 6-foot wave to produce a 30-foot-tall updraft. The birds typically glide until the wave breaks, then soar back into the sky, only to quickly drop back down to repeat a process that isn’t very taxing on them physically.

“They’re using the environment to make their lives easier; it’s like riding a bike downhill,” said Ian Stokes, a doctoral student at UCSD’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography. Stokes is the lead author of the new model, which was recently published in the journal Movement Ecology, with lots of guidance from his adviser, Scripps oceanographer Drew Lucas. The model is basically a set of mathematical equations that enable scientists to determine how much energy pelicans can save by gliding on the updrafts. In some cases, the birds save comparatively little energy. In other cases, they don’t have to flap their wings at all. The model factors in everything from the height and periodicity of waves to how close pelicans fly to the ocean’s surface. Stokes began developing the model at UC Santa Barbara, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in physics. To his surprise, Lucas encouraged him to develop the idea further when he arrived in La Jolla.

Take a walk along the beach in San Diego County and you’re likely to end up marveling at the majesty of birdlife. Sleek brown pelicans descend from the sky and glide — often hundreds of yards at a time — just above the ocean’s surface, in front of building waves. It’s a common phenomenon that was not deeply understood — until now. UC San Diego has come up with the most detailed theoretical model yet for describing and quantifying how pelicans harness the ocean and winds with little or no need to flap their wings.

The bottom line: pelicans — which have wingspans up to 7.5 feet wide — are fantastically skilled at gliding atop the updraft of wind that is created by moving waves. The waves get steeper as they near shore, further strengthening the updraft. The bigger the wave, the bigger the lift. And pelicans know it; they get as close as possible to the ocean’s surface, where the updraft is strongest. It’s not unusual for a 6-foot wave to produce a 30-foot-tall updraft. The birds typically glide until the wave breaks, then soar back into the sky, only to quickly drop back down to repeat a process that isn’t very taxing on them physically.

“They’re using the environment to make their lives easier; it’s like riding a bike downhill,” said Ian Stokes, a doctoral student at UCSD’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography. Stokes is the lead author of the new model, which was recently published in the journal Movement Ecology, with lots of guidance from his adviser, Scripps oceanographer Drew Lucas. The model is basically a set of mathematical equations that enable scientists to determine how much energy pelicans can save by gliding on the updrafts. In some cases, the birds save comparatively little energy. In other cases, they don’t have to flap their wings at all. The model factors in everything from the height and periodicity of waves to how close pelicans fly to the ocean’s surface. Stokes began developing the model at UC Santa Barbara, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in physics. To his surprise, Lucas encouraged him to develop the idea further when he arrived in La Jolla.

“I thought it was a silly little thing — not a significant problem,” Stokes said. “I thought we needed to focus on climate change.” In a very real sense, that’s what he’s been doing. “This work is teaching us about how the atmosphere and the oceans interact,” Lucas said. “And how they exchange energy. That’s what’s involved in climate change. We’re learning important things about ocean and atmospheric physics.”

The new model also could help biologists and ornithologists who are more broadly studying the metabolic cost of flight among birds. Stokes’s new study involves one of the most beloved birds known to exist. Pelicans can ascend 60 to 70 feet into the air, where they’re able to easily see the fish they prey on. And they can fly up to 30 mph, often in handsome V-shaped formations.

“I love the fact that they are a mix of elegance and awkwardness,” said Nigella Hillgarth, a nature and wildlife photographer who formerly served as director of UCSD’s Birch Aquarium. “They can look awkward when moving about on land, and sometimes when they’re fishing. But they’re incredibly graceful when they’re gliding through the air. I often gaze at the pelicans until they fly so far I can barely see them any more as they skim over the water.

PIC OF THE WEEK:

Had a buddy recently pack up and move to Central America. Was it the cheaper cost of living down there? The laid back lifestyle? The natural beauty? How about the warm air and ocean? Anything else I missed?...

Keep Surfing,

Michael W. Glenn

Everything To Everyone

NFL's Mr. Irrelevant 2021

So Many Waves, So Little Time (TM)

Michael W. Glenn

Everything To Everyone

NFL's Mr. Irrelevant 2021

So Many Waves, So Little Time (TM)